The Book of Concord – Conclusion

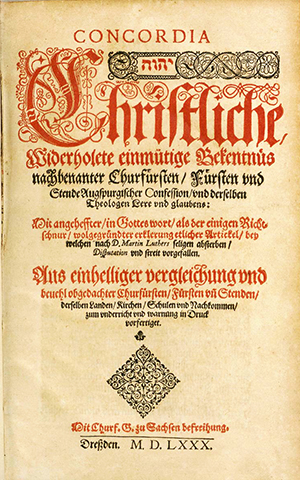

The Book of Concord.

“Don’t think I have come only to bring peace,” our Lord once told His followers. “I have not come to bring only peace, but also a sword” (Matt 10:34). For the world, proclaiming the Gospel of Jesus Christ has been both suture and sword, mighty fortress and stumbling stone, the fragrance of life and odour of death, a word that creates one, holy, united people from all nations and a word that can set father against son and daughter against mother. Peace—and a sword. What was true in our Lord’s day was true in the reformer’s days and is true today.

Remembering that, we are not surprised not all welcomed the Book of Concord with shouts of “Gott sei dank! (“Thanks be to God!”). Book titles like Discord, Dialogue, and Concord and Concordia controversa remind us that it was the life-threatening lack of unity and agreement that called for the book’s publication. And, like every confession of the Truth, it brought peace—and a sword.

Three points about the impact of the Book of Concord remain particularly relevant for us today:

First, it is the Book of Concord. In their fierce struggle to bring about concordia (harmony) among Luther’s followers, men like Jacob Andreae, Martin Chemnitz, David Chytraeus, and Nicholas Selnecker did not simply produce a new confessional statement. They gathered in one volume confessional writings that had provided guidance and unity through some of the church’s most difficult times (e.g., the creeds, the Augsburg Confession and its Apology, the catechisms of Luther) and confessional writings that could help the church address her current divisive issues. Moreover, these statements of faith point to the Holy Scriptures as the wellspring from which all true and pure confession flows. New challenges had not rendered old statements irrelevant; rather, the ongoing struggle for unity forced the church to return to these earlier statements of faith and, through them, to the Word of God. The Book of Concord was compiled in the Reformation spirit: this was no attempt to introduce a new teaching, but an attempt to understand and apply the self-revelation God gave the world in His Son, Jesus Christ.

Second, the unity sought by the Book of Concord was not simply an agreement among theologians but a true concordia among the people of God. The story of the Formula of Concord begins and ends with appeals to parish pastors and the members of their congregations. The divisions were serious and the issues literally of vital importance, but the problems could not be solved in the faculty lounges and administrative board rooms of the day. The battle for concordia had to be waged and won in sanctuaries and living rooms. Andreae’s sermons and Fuger’s “catechism” (A Brief, True, and Simple Report of the Book Called the Formula of Concord) are evidence that those working for unity and peace had realized this truth. In her study of Fuger’s efforts toward unity, Irene Dingel notes: “Not only pastors and scholars were to support the new book of confessions, however. The ‘simple folk’ were also supposed to grasp that what was at stake here was the preservation of the truth of the gospel and defense against false teaching.”

Robert Kolb makes a thought-provoking observation in an article on the Book of Concord’s index, tracing the development in meaning of “body of teaching,” in Latin, corpus doctrinae. The ten documents composing the Book of Concord were seen as a body of teaching which defined the public faith of a particular group of Christians in a particular place. In earlier times, the term had meant those documents in which a particular rule of faith could be found. Earlier still, the term simply referred to that rule of faith (analogia fidei), or interpretive principle, by which the Faith could be understood, taught and applied.

And that brings us to the final point, real concordia is a matter of the heart. These writings strive to bring about in readers a unity going far beyond simply saying, “We accept this and that.” It is a unity brought about by making new hearts and transforming minds. It is a oneness coming from being born again and shows itself in a new way of thinking about and understanding creation, the history of the cosmos, the purpose of “it all,” and, most importantly, God’s Word. This oneness of heart and mind arises when we understand that all Scripture testifies of Jesus Christ. It is the oneness coming from believing and confessing that the message of the Scriptures expounded in the Confessions is that we are justified by grace through faith in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Such unity can only come about through the reconciling ministry of the Spirit of Christ among us. In the closing decades of the sixteenth century, the Spirit brought such unity to thousands of Lutheran pastors and their congregations through the publication of The Book of Concord. But some could not accept this book immediately, and some could never accept it. The Lord’s work to unite His people in a faithful confession of His truth would continue—and continues through us.

We give the last word to Martin Luther who closes a letter to Martin Bucer, sent from Wittenberg and dated 22 January 1531, with these words: “May the Lord Jesus enlighten us, and may he make us perfectly of one mind; for this I pray, for this I sigh, for this I long. Farewell in the Lord.”

Rev. Dr. Jeffrey Oschwald

The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod

(Originally published by the International Lutheran Council in 2005)