← The other Saints of the Reformation

Martin Luther: The Father of the Reformation

Rev. Dr. Edward G. Kettner

Originally published in The Canadian Lutheran, September/October 2015

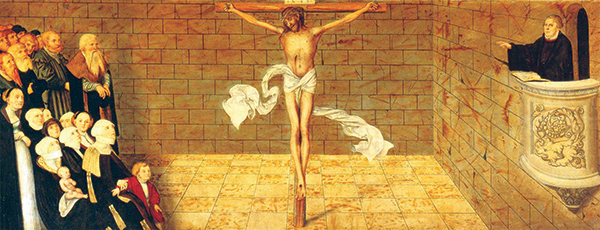

October 31, 2017 will mark the 500th anniversary of what is considered the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. On that date Martin Luther nailed 95 theses for debate concerning the issue of indulgences onto the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The printing and distribution of these theses created a firestorm which led to the reformation of the church, not only in external corruption, but in the heart and core of the Gospel: the biblical truth that we are justified (declared righteous) before God not on the basis of our good works but by faith in the God who declares us righteous because of Christ.

October 31, 2017 will mark the 500th anniversary of what is considered the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. On that date Martin Luther nailed 95 theses for debate concerning the issue of indulgences onto the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. The printing and distribution of these theses created a firestorm which led to the reformation of the church, not only in external corruption, but in the heart and core of the Gospel: the biblical truth that we are justified (declared righteous) before God not on the basis of our good works but by faith in the God who declares us righteous because of Christ.

Early Life

Martin Luther was born November 10, 1483 in Eisleben, the second son of Hans and Margaretta Luder. He was baptized the next day, the feast day of St. Martin of Tours, after whom he was named. In 1484 the family moved to Mansfield. His father, who began in poverty, soon purchased two smelting furnaces, and provided a good living for his family, and even became a councilman (“burgher”), hoping to provide a good education for his children.

Martin’s education began in Mansfeld, where he began to learn Latin, along with the Ten Commandments, Lord’s Prayer, hymns, and prayers. Because his father had professional hopes for him, he was sent in 1497 at the age of fourteen to the Franciscan school at Magdeburg. After a year there he was sent to school in Eisenach where he had relatives. However, he got no financial support from his relatives, either because they would not, or simply could not, support him. By God’s grace, he was taken in by Ursula Cotta, wife of Conrad Cotta, who provided a place for him to stay. Freed from want, his life as a scholar blossomed, as he grew in knowledge of science, literature, and the fine arts, singing, and playing both the lute and flute.

From Eisenach he went to university in Erfurt in 1501. He had acquired a thirst for knowledge while at Eisenach, and his father wanted him to study law. At Erfurt he learned dialectics, a strongly disciplined style of philosophy which prepared one for argument and disputation. After two years at Erfurt, at the age of twenty, he received the degree of Bachelor of Arts, and in 1505 received the Master of Arts. The discipline made him realize how far short he fell of the true holiness that God desired of him, and of all people.

Luther’s life changed through several brushes with death: a serious illness brought about by exhaustion when studying for his bachelor’s examination, and an injury when the sword he was wearing cut a major artery in his foot as he was heading home for a visit at Easter in 1503. He was also affected by the murder of a close friend, Alexis, at university, which brought home the reality that death could come at any time.

When he was heading back to Erfurt from home in the summer of 1505, where he was already lecturing at the university as part of his program of study of law, he was thrown to the ground by a lightning bolt that struck nearby. In terror he cried out, ‘St. Anne help me! I will become a monk!’ The terrors of conscience that this event aroused led him now to seek holiness as much as he had previously sought knowledge. He abandoned the life of the university and entered the Augustinian cloister in Erfurt on August 17, 1505, throwing himself with zeal into the ritual and routine, and doing so in order to save himself.

After a brief apprenticeship doing the most menial of tasks and of begging, he was freed to return to studies, this time in theology. He spent time in the God’s Word, meditating upon it, desiring to learn perfectly God’s will, studying Hebrew and Greek as well. However, his conscience tormented him whenever he missed the prayers of the day because of his study, and he would strive to make them up. His fears continued to mount. We see in early Luther a combination of fierce piety created and driven by the Law, which at this point even his scholarship did not abate. Told to seek comfort and righteousness by his own works, he was driven even more into despair.

In the midst of his struggles he was befriended by Johann Staupitz, Vicar General of his order, who had gone through similar struggles, and who preached grace and faith to Luther. Staupitz was a scholar, and friend of Frederick the Wise, who had made him the founding director of the University of Wittenberg and the first dean of the theological faculty. (The university was founded in 1502). Though he did not yet fully comprehend the Gospel, Luther had begun to believe God actually provided forgiveness for him in the blood of Christ, and was able to declare, “I believe in the forgiveness of sins.”

Ordination came after two years in the monastery, on May 2, 1507. He became a professor at Wittenberg at the end of 1508 teaching physics and dialectics. He renewed his study of the languages and of the Bible hoping that he would in the end be able to teach theology. He received the Bachelor of Divinity in March 1509. He also was called upon to preach, ultimately serving as preacher for the city church, and later for the castle church.

Already he was becoming disillusioned with Rome. He had made a journey to Rome around 1511 to represent his order before the pope. He had previously thought Rome was a place of sanctity, but saw that it in fact was a place of corruption.

He finished his doctoral work in 1512 and began to teach theology. He lectured first on the Psalms and after that, on Romans. In these earliest lectures it seems that he still did not fully grasp the Gospel, still speaking of some kind of righteousness within us that saves us. Yet Luther himself said that it was in the study of Romans 1 that he found release as he realized that the righteousness which saved was a righteousness apart from the Law—the righteousness that saves is the righteousness of Christ!

The Ninety-Five Theses were precipitated by the indulgences controversy. Pope Leo X had decreed permission for the sale of plenary indulgences, which granted the purchaser, or the person for whom they bought one, full remission of time in purgatory. Johann Tetzel was charged with the sale of them in the region. The purpose was to pay for Albrecht of Mainz’s bishoprics (archbishop of Mainz and of Magdeburg, and bishop of Halberstadt), and to also support the remodeling and expansion of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

The Ninety-Five Theses were presented simply as theses for debate as was the custom of the universities at that time. He nailed them to the door of the castle church, not as an act of protest, but because that is where such notices were published. They were not an attack on church or pope; in fact, he sincerely believed that if the pope knew what abuses were taking place that he would be appalled. (Sadly, he wasn’t.) In the end, we see here the work of a man who desired the moral reform of the church. The fullness of the Gospel was not yet present, but he was getting there. The disputation never took place, but the theses were quickly printed and spread throughout Germany and Europe. Indeed, without the printing press, the Reformation would have had great difficulty gaining ground.

As attention grew, Luther continued to prepare theses for debate which showed growth in understanding what the Gospel was really about. The Heidelberg theses were prepared for a general chapter meeting of the Augustinians in Germany, held at Heidelberg in April of 1518. Here Luther laid out the theses for dispute that first addressed the concept of what it means to be a “theologian of the cross.”

About a year later, the Leipzig debate with Johann Eck—one-time friend of Luther—dealt with the question of the church and papacy, as well as other issues raised by Luther’s theology. In Luther’s rejection of the papacy, Eck accused Luther of being a “Hussite,” a follower of Jan Hus, the Bohemian reformer of the early 1400s. In the end, Luther admitted privately, “We are all Hussites.” This was the key revelation to Luther at these debates; he clearly now sought the overthrow of the papacy and to declare Christ alone to be the head of the Church. The principle stands, that popes and councils can err.

While many of these disputations stand apart from his lecturing duties at the university, Luther certainly understood them to be a part of his call as a doctor of the church. As a result of his rejection of the papacy as the head of the church, Luther was excommunicated on June 15, 1520. His response included his treatise “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church,” where Luther asserts the importance of the sacraments as vehicles of God’s unmerited favor to the individual, to be received by faith. Through all of this, his desire was to ensure that God’s people understood that they were saved through faith in Christ, not through their own righteousness.

The Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms

Luther was called upon to present himself to the Imperial Diet at Worms in 1521 to recant his teachings. Here he made his famous stand, declaring that he would not recant his teachings unless compelled to do so by the Scriptures and by clear reason. The emperor’s edict afterwards condemned the teachings of Luther and authorized his arrest after the safe conduct he had been granted had expired. Following the Diet, on his way back to Wittenberg, he was “kidnapped” by servants of Frederick the Wise, and held in “exile” at the Wartburg Castle, overlooking Eisenach. It was here, in confinement for a little over a year, that he began to translate the Bible into German. He desired that the people be enabled to read the Word of God in their own language, and to do so in a way that sounded as if it had originally been written by a German.

Luther’s zeal for the pure Gospel led him into conflict also with other reformers. Ulrich Zwingli from Zurich, and later John Calvin of Geneva, rejected the idea that the Holy Spirit works through means: the preached Word and the visible words which are the sacraments. Particularly against Zwingli, Luther repeatedly stated that in the Lord’s Supper Christ gives His true body and blood for the forgiveness of our sins, and that it is not merely a memorial meal. For Luther, faith clings to the word of promise outside of us, and is not focused primarily inwardly on our feelings. In the Word, God is at work.

Luther’s focus on the Gospel extended to life in this world. He was instrumental in freeing many young women from the convents who had realized the impossibility of keeping their vows, and worked with his colleagues to find husbands for them. While not intending to get married himself, he in the end married former nun Katerina von Bora on June 13, 1525. The union was blessed with six children. One of the most sorrowful events in Luther’s life was the death of his daughter Magdalena at the age of fourteen.

Christian Education

What with all of his duties as professor and doctor of the church, Luther realized that the education of the Christian (and of pastors as well) was absolutely necessary if they were to believe and to teach the faith. To that end, in 1529 he took upon himself to preach on the central parts of the faith and to prepare two catechisms on these parts: the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, Baptism, Confession, and the Lord’s Supper. The Small Catechism also included a “Table of Duties” and some basic prayers, to assist one in living one’s life in vocation. It was meant to be learned and memorized, and was made in chart form to be hung on the walls of home, church, and school, so that those words would be always before their eyes. The Large Catechism gave more detailed explanations, and could serve as a guide to parents and pastors as they taught their children and households.

The 1530s saw Luther solidify his teachings of the Gospel of free grace in Christ, and repeatedly affirm that those words which he wrote were his solid confession of faith from which he would never depart.

Luther constantly travelled, as a doctor of the church, trying to heal divisions, both political and churchly. On January 23, 1546, Luther left to work to settle a dispute among the three counts of Mansfield. Meeting in the town of Eisleben, where Luther had been born, he managed to work with them to bring about some sort of agreement. But in the end, the journey and the work were too much for him, and he died the morning of February 18, 1546 in Eisleben, having firmly confessed his faith in Christ and standing firm on the doctrine he had taught. In his pocket was found a scrap of paper with the words, “We are beggars, it is true.” His body was buried near the pulpit in the Castle Church in Wittenberg.

Luther’s legacy lives on in that we desire, as he did, to retain our connection to the church of the ages through the preaching of the Gospel and the administration of the sacraments as instituted by Christ. Though we do not deny the importance of religious experience, like Luther we must recognize that true experience is created by the message of the Gospel, not merely be the cultivation of certain emotions. May God keep us steadfast in His Word!